Historic Market Overview

H1 2021 benefited from global demand recovery, which is expected to gain momentum in H2 2021. This is because the Chinese economy remained robust and economic recovery took hold in other countries around the world.

Vanadium prices have recovered and should remain steady as long as the economic recovery persists.

Governments around the world have announced different measures to revive their economies after the impact of COVID-19, and, with vaccine availability and widespread distribution, the global economy is expected to recover.

The potential headwinds are:

- Easing of stimulus in China, which may reduce Chinese vanadium consumption.

- Setbacks in the global recovery from COVID-19, as new variants are seen across the globe.

The demand for VRFBs is expected to increase, based on a higher number of installations in 2020 and 2021 as well as announced projects for the rest of the decade. This translates into a higher gigawatt / hour (GWh) forecast and higher vanadium demand.

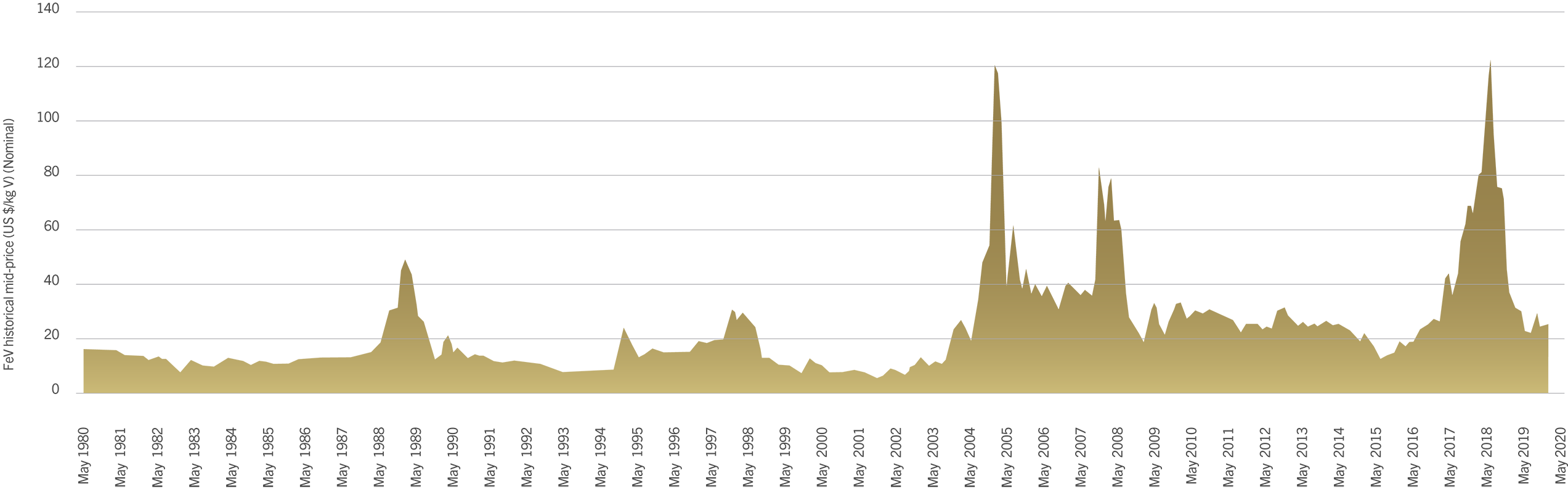

Vanadium Price

2020 was characterised by the divergence in economic performance and steel production between China and the rest of the world, respectively depicting strong growth and strong decline. This was reflected in the vanadium market, with increased imports in China that built a Chinese price premium.

The robust vanadium demand and rising prices at the end of 2020 continued in 2021 across all key markets. The recovery was driven by higher steel-mill capacity utilisation rates and low warehouse stocks. The vanadium price has continued to rise, with increased demand in Europe and the US.

Supply

Most of the vanadium supply volume, on a unit basis, came from Chinese slag producers, whose production of slag increased. This resulted from higher steel output on the back of fiscal stimulus that the government introduced in late March 2020 to fast-track an economic recovery.

These measures included increased infrastructure spending, which translated into record steel production.

China became a net vanadium importer for five months in 2020: June, July, August, October and November. This absolute increase in steel production has resulted in Chinese co-producers operating at near capacity, limiting the scope for further vanadium production growth from this source.

Supply Growth

Outside China, production increases were recorded by primary producers in South Africa and Brazil. Stone coal production declined slightly year-on-year as low prices disincentivised production. Although stone coal producers could be re-incentivised by higher prices, environmental, financial, and technical constraints remain.

Despite the significant increase in vanadium slag production, several efforts by the Chinese government to rationalise its steel industry and cut pollution may impose further constraints on vanadium co-production steel plants. Meanwhile, stone coal production will continue to be limited by environmental restrictions. The result is a constrained growth outlook for Chinese vanadium production from co-producers (already operating at near capacity) and stone coal vanadium producers. The constraint is exacerbated by the ban on vanadium slag imports into China.

Secondary production is poised to increase supply in the medium term due to International Maritime Organisation (IMO) 2020 regulations requiring more refining catalysts. However, it remains a higher-cost form of production than primary and co-production. The new supply could either displace the projects with weaker economics or create a larger and more durable surplus. Secondary production is limited, not by processing capacity but the availability of the necessary feedstock and high production costs. The supply of secondary materials is derived mainly from spent catalysts associated with the processing of crude oils and oil sands, the manufacture of various acids, ash and residues from the combustion of oils and coals, and some residues from alumina production – particularly in India.

Supply growth can be considered across three categories:

- Capacity expansions of current producers

- Restarting production plants that had been mothballed

- Greenfield project development

Capacity expansions have the highest probability of realisation, with the lowest capital requirements and quickest path to production. New greenfield projects face the most significant hurdles. Most of the recent greenfield projects announced for development are of a co-production or multi-commodities nature, suffer from relatively low grades, require substantial capital, and have a relatively stable and higher price outlook than recent prices indicate.

Leading Producers

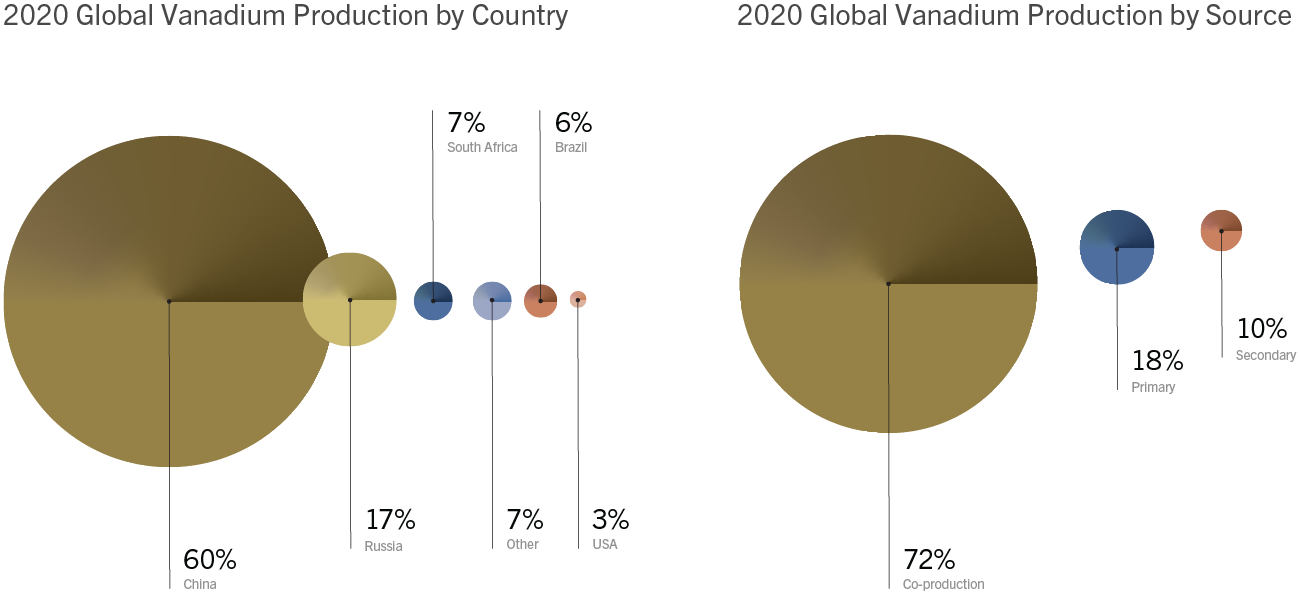

In 2020, global vanadium production increased to 116 128 mtV from 109 643 mtV in 2019.

This increase was due to higher slag production in China, driven by:

- Increased crude steel production, supported by the Chinese government’s stimulus measures (primarily driven by infrastructure spending), which translated into record steel production of 1 065 Mt, a 7% year-on-year increase.

- High seaborne iron ore prices (iron ore prices rose to their highest levels in the last five years, at over US$150 / t) by December 2020. This was driven by China’s strong demand, as well as constrained global supply. As a result, Chinese steel mills used more domestic vanadium titaniferous magnetite ore.

China is the world’s top vanadium producer – accounting for 60% of the global vanadium supply in 2020. Most of its vanadium was derived from co-production.

Russia is the second-largest producer and South Africa the third-largest, accounting for 17% and 7% of 2020's supply, respectively.

South Africa’s vanadium derives from primary production from Bushveld Minerals (Bushveld Vanadium) and Glencore.

Demand

Total vanadium demand is dominated by the steel industry, which accounted for 91% of total demand in 2021 and will remain the largest source of vanadium demand in the future.

Global vanadium consumption increased from 109 835 mtV in 2019 to 112 157 mtV in 2020, supported by increased infrastructure spending in China, which resulted in higher steel production, in turn supporting vanadium demand.

During the period, Bushveld Minerals took advantage of the robust vanadium demand and higher prices in China than in other jurisdictions by diverting a larger portion of its sales to China in H1 2020.

The vanadium demand from the North American and European steel and aerospace industries declined during the period, due to the pandemic and associated plant shutdowns.

The increase in consumption was primarily driven by the Chinese government’s stimulus for infrastructure spending and increased intensity of use of vanadium in steel, as enforcement of rebar standards improved during 2020.

According to Roskill, vanadium demand in the steel market will grow at a CAGR of about 2,7% through to 2030, with global vanadium demand from steel reaching approximately 136 000 tonnes by 2030.

While vanadium demand will be underwritten by the growing intensity of use of vanadium in the steel market, the energy storage industry offers significant demand upside.

An example is Nusaned Investment, a Saudi Arabian-based company that entered into a joint venture with Germany-based technology company Schmid Group to focus on manufacturing and technology development.

Trade Expansion Act

Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, as amended (19 USC 1862), provides the president of the USA with the ability to impose restrictions on certain imports, “based on an affirmative determination by the Department of Commerce that the product(s) under investigation is imported into the United States in such quantities or under such circumstances as to threaten to impair the national security”.

In November 2019, a petition was filed by two domestic vanadium producers (AMG Vanadium and US Vanadium LLC) alleging that vanadium is imported into the USA in quantities or under circumstances that threaten to impair national security.

In May 2020, in response to the petition, Bushveld Minerals and a clear majority of other vanadium industry stakeholders responded in opposition to arguments that vanadium imports threaten the national security of the USA.

They noted, in particular, that Nitro Vanadium has been imported into the US in stable volumes, over several decades, and in part highlighted that even the domestic USA producers of vanadium are non-integrated processors that import a significant portion of their feedstock. Bushveld Minerals’ sales volume to the USA accounted for 34% in 2020.

The US Commerce Department submitted the results of its investigation to the president in February 2021. To date, neither the headline findings nor the report itself has been made public.

By 22 June 2021, the president of the USA had made no official statement about the Section 232 investigation into vanadium imports. It is now being assumed that there will be no changes to the current situation regarding the importation of vanadium into the USA.

Forecast

We retain the view that supply remains concentrated and constrained. Limited new supply is expected from greenfield projects and co-production is still primarily driven by steel and iron ore fundamentals.

With record steel production and iron ore prices close to their all-time high, China’s slag producers are expected to have increased their output by about 9% in 2020. Although the high iron ore price provides an incentive for steel mills to use more domestic vanadium titaniferous magnetite ore, Chinese co-producers are operating close to capacity, restricting their ability to produce more vanadium.

In addition, several efforts by the Chinese government to cut pollution may impose further constraints on vanadium co-production steel plants. These initiatives include the reduction of excess steelmaking capacity targeting highly polluting, high-cost plants, and the conversion of blast furnace operations to electric arc furnace technologies, which will increase the role of scrap iron in steel making and reduce the overall demand for iron ore.

Due to quality, domestic iron ore supply, and environmental restrictions on both steelmakers and co-production vanadium producers, can be expected to see a greater reliance on haematite (non-vanadium bearing) iron ore for steel making among co-producers, which will limit vanadium slag production growth.